Ophiocordyceps stylophora - Bad News if You're a Click Beetle

- Oct 5, 2025

- 5 min read

Good evening, friends,

This week we’re looking at a fungus we found back in early September, but with all the forays and festivals in September, we haven’t taken the opportunity to focus on this species yet. Regardless, this will certainly go down as one of my favorite finds of the year.

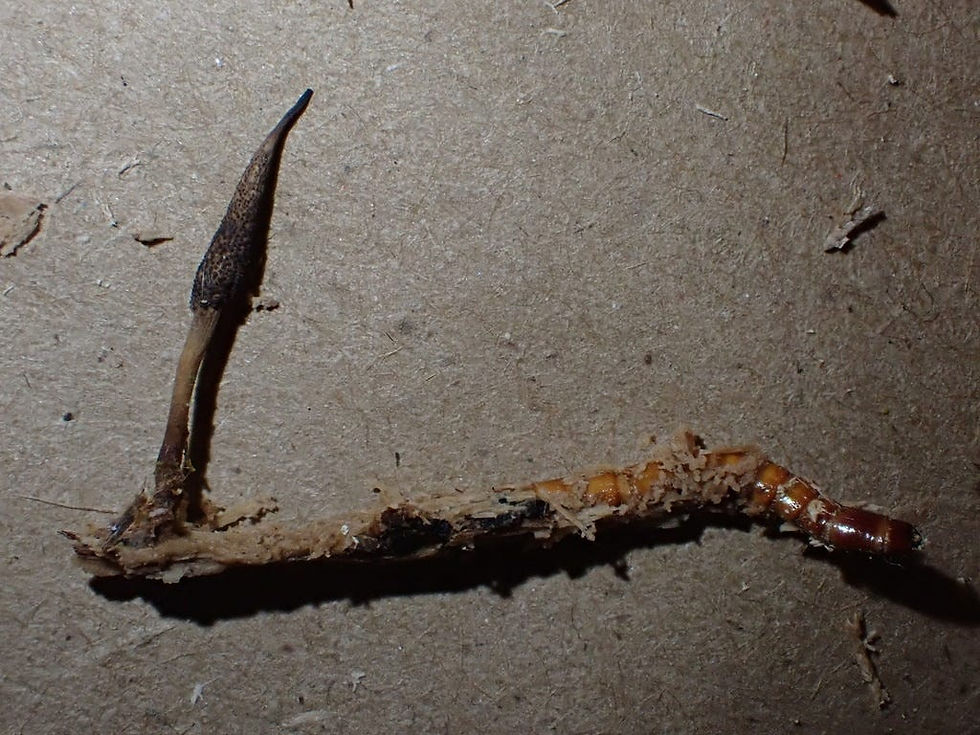

The entomopathogenic fungus, Ophiocordyceps stylophora, was barely visible as it poked through the moss that blanketed a decomposing log. Our friend from Utica, Rich Tehan, identified the species, and this creepy little finger is a perfect fit for the first fungus of October (not just based on looks, but diet too).

Fun Facts

O. stylophora is an entomopathogenic fungus (an insect pathogen), and these fungi are colloquially referred to as “Cordyceps”. Cordyceps have gained recent cultural appeal for their medicinal properties, and HBO even made a show (based on a video game) about the concept of cordyceps that infect humans. Here’s a video on how the “zombie fungus” hijacks an ant’s body.

Fortunately for us, these Cordyceps fungi parasitize insects, and sometimes other fungi, but not humans. It’s also important to note that the majority of cordyceps do not “zombify” their host, but will infect the insect as it undergoes metamorphosis from larval stage to adult. Some entomopathogenic fungi are even used as insect control, like Entomophaga maimaga on spongy moths and Beauveria bassiana on spotted lanternflies.

Etymology

The fungus was originally described as Cordyceps stylophora. The genus Cordyceps comes from the Greek word kordyle, meaning “club”, and the Latin suffix -ceps, meaning “head”. The prefix Ophio-, from the Greek ophis, means “snake”. “Snake-like clubhead” describes the shape of a lot of cordyceps fruiting bodies, like an upside-down bowling pin, but that’s not necessarily the case with ours.

The species epithet Stylophora comes from the Greek Stylo- meaning “pillar” or “column”, and -phora meaning “carrying” or “bearing”. The fruiting bodies of Ophiocordyceps stylophora are thin, column-like, and taper off at the top like an elongated Hershey’s kiss on a stick.

Ecology

Something I tried to emphasize yesterday during my presentation on burn fungi was that fungi can exist in different ecological roles at different points in their life. For example, burn fungi can exist as endophytes living inside moss for decades as they wait for a wildfire to burn the forest and create the charred organic matter which they will digest and use to produce mushrooms. That’s not too dissimilar from how some of these entomopathogenic fungi exist.

The question is how does the insect get infected by the fungus? I couldn’t find anything specific about Ophiocordyceps stylophora’s life cycle, but there is a lot of information and research on the closely related Ophiocordyceps sinensis — a popular medicinal fungus in Nepal and China.

The Chinese name for O. sinensis is 冬虫夏草, which translates to “summer grass winter worm”. The fungus lives as an endophyte in the roots and blades of grass (and other plants) where it helps the plant resist infection and drought in exchange for a safe place to live. Then, the hungry caterpillar of a ghost moth (Thitarodes) comes along and eats some of the plant matter which harbors the endophytic fungus. The Asian O. sinensis digests the insect while it’s still in the larval stage (a caterpillar), as does O. stylophora.

Our fungus, O. stylophora, infects the larva of click beetles (Elateridae), also known as wireworms. Wireworms have a diverse diet, depending on the specific species, and eat everything from decaying material in rotting logs to plant roots to other insect larvae. I couldn’t find the specific endophytic relationship for O. stylophora, and where the point of introduction to the wireworm would occur, but I imagine it’s through something the wireworms eat.

Some fungi aren’t introduced through consumption, however, rather the fungal spores land on the insect and germinate. The fungus begins to colonize the insect’s cuticle and produces appresoria, which apply “strong mechanical pressure” on the insect’s shell and release enzymes to help dissolve the cuticle. The fungus then enters the insect and begins to eat the insect from the inside. Fascinating and unsettling.

O. stylophora appears in the late summer across the northern hemisphere, but they’re so small and subtle that they’re infrequently found.

NY Fungus Fest

I was down in NYC yesterday to attend and participate in the New York Mycological Society’s Fungus Festival. It was a lot of fun, and if anything too short, but certainly too hot. I tried to absorb as much programming as I could while finding shade and slinging some t-shirts. It was great to see a lot of friends, meet some new folks, and talk about burn mushrooms. Thanks to the New York Mycological Society for hosting and continuing to provide accessible fungal education for all.

Mushroom Events This Week

6PM on 10/8: I’m excited to give a presentation on the Magic of Mushrooms for the Stamford Land Conservation Trust’s annual meeting, taking place at the Stamford Museum and Nature Center in Stamford, CT. I’ve been involved with the organization since 2017 and am very excited to present to the group.

And if you’re in the Boston area, there’s a new mycology project underway. Check out the Community Mycology Collective and reach out to Jula for more details about the first meeting on October 17th:

There’s a full moon out right now,

Aubrey

References:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/ophiocordyceps-sinensis

Zhengyang Wang, Meng Li, Wenbin Ju, Wenqing Ye, Longhai Xue, David E. Boufford, Xinfen Gao, Bisong Yue, Yong Liu, Naomi E. Pierce,

The entomophagous caterpillar fungus Ophiocordyceps sinensis is consumed by its lepidopteran host as a plant endophyte, Fungal Ecology,

Volume 47, 2020, 100989, ISSN 1754-5048, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.funeco.2020.100989.

https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/905165-Ophiocordyceps-stylophora